Here is a maths drawback starring singer Lata Mangeshkar, composer R.D. Burman, lyricist Majrooh Sultanpuri, and director Prakash Mehra.

In the winter of 1972, their music ‘Kaanta Laga’ debuted, making them X sum of money. Then, in 2002, got here a remix, arguably probably the most well-known iterations, picturing a sultry Shefali Jariwala in a black tank and braids, controversially flipping by a porn journal. Later, in 2016, artistes Neha Kakkar, Honey Singh and Tony Kakkar determined to “revive the party anthem” with yet one more rendition. Every remix, launched by well-known music labels or impartial homes, cashed in on the unique genius: the lyrics, the composition, the voice.

Asha Parekh in ‘Kaanta Laga’ (1972) and (proper) Shefali Jariwala within the 2002 remix

‘Kaanta Laga’ lives as a cultural sensation, however what does X characterize? How a lot cash ought to the music’s authentic authors obtain? Much just like the music, the query of music royalties is timeless. Over the final decade, lyricists and composers have tried to resolve X, preventing for recognition within the courtroom of legislation and public opinion.

They lately inched nearer to an answer. On April 28, the Bombay High Court handed a historic verdict directing FM radio stations Radio Tadka and Radio City to pay royalties to a music’s “authors” (lyricists, composers and singers) for utilizing copyrighted music — setting a authorized precedent for stations throughout India to do the identical. “The value of radio is far greater in the music industry if you look at the revenue, and yet, the radio industry has been undercutting them and not paying them their dues,” says Amit Gurbaxani, a Mumbai-based music journalist.

“This is a big victory for the musical family. We are very thankful to the Mumbai High Court for recognising our efforts and hard work behind musical creation. This is a huge inspiration.”Kanukuntla Subhash ChandraboseLyricist for RRR

The judgment grants legitimacy to the rights of lyricists and composers — reaffirming that the possession of a music lies not simply with movie producers and labels, but additionally artistes who are sometimes invisibilised throughout the music industry. “The judgment… is absolutely historic,” says singer-composer Anu Malik (suppose ‘Julie Julie’ in 1987 or ‘Oonchi Hai Building 2.0’ in 2018). “It is for every lyricist, every composer, who puts their heart and soul into creating music.”

A decades-long authorized battle

Authors promote their creation to manufacturing homes for a one-time charge, who in flip promote it to music firms. The music then takes a lifetime of its personal, streaming on radios, punctuating advertisements, beaming off cellphones as ringtones. “When rights are bought out, only the labels make money, not the people who are creating the music,” Gurbaxani notes.

“We have to explain to [people], over and over, that we are the authors of a song, and that we are worthy of the respect and the credit that comes with it. It is depressing, it is frustrating, it is exhausting.”Varun GroverLyricist

Copyrights throughout the music industry might be separated into pre- and post-2012 phases, cleaved by the passing of the Copyright (Amendment) Act. The amendments have been a end result of a authorized struggle that started in 1977, led by the Indian Performing Rights Society Limited (IPRS), a licensed copyrights collective which gathers royalties on behalf of members pan-India. It took 35 years, a number of courtroom instances and one authorized modification for the legislation to recognise creators’ rights: a lyricist or composer holds copyrights to their work, they’ve a proper to royalty — every time the music is performed (whether or not it’s authentic, a remix, or a rehash through reels or movies) — and, most importantly, this proper can’t be transferred. The association was to divide royalties 50:50 between the producers and authors.

It was historic. But historical past can also be simply disputed. Between 2012 and 2023, IPRS needed to manoeuvre authorized loopholes, and struggle FM stations and producers to show that the safety granted to creators was certainly theirs to wield. The Bombay High Court’s judgment was the primary to recognise this.

“This judgment could become a precedent for many artistes and get them the due recognition as authors of a piece of work, and therefore make sure they earn royalty on it,” says Tatsam Mukherjee, a movie critic who has been carefully following the talk.

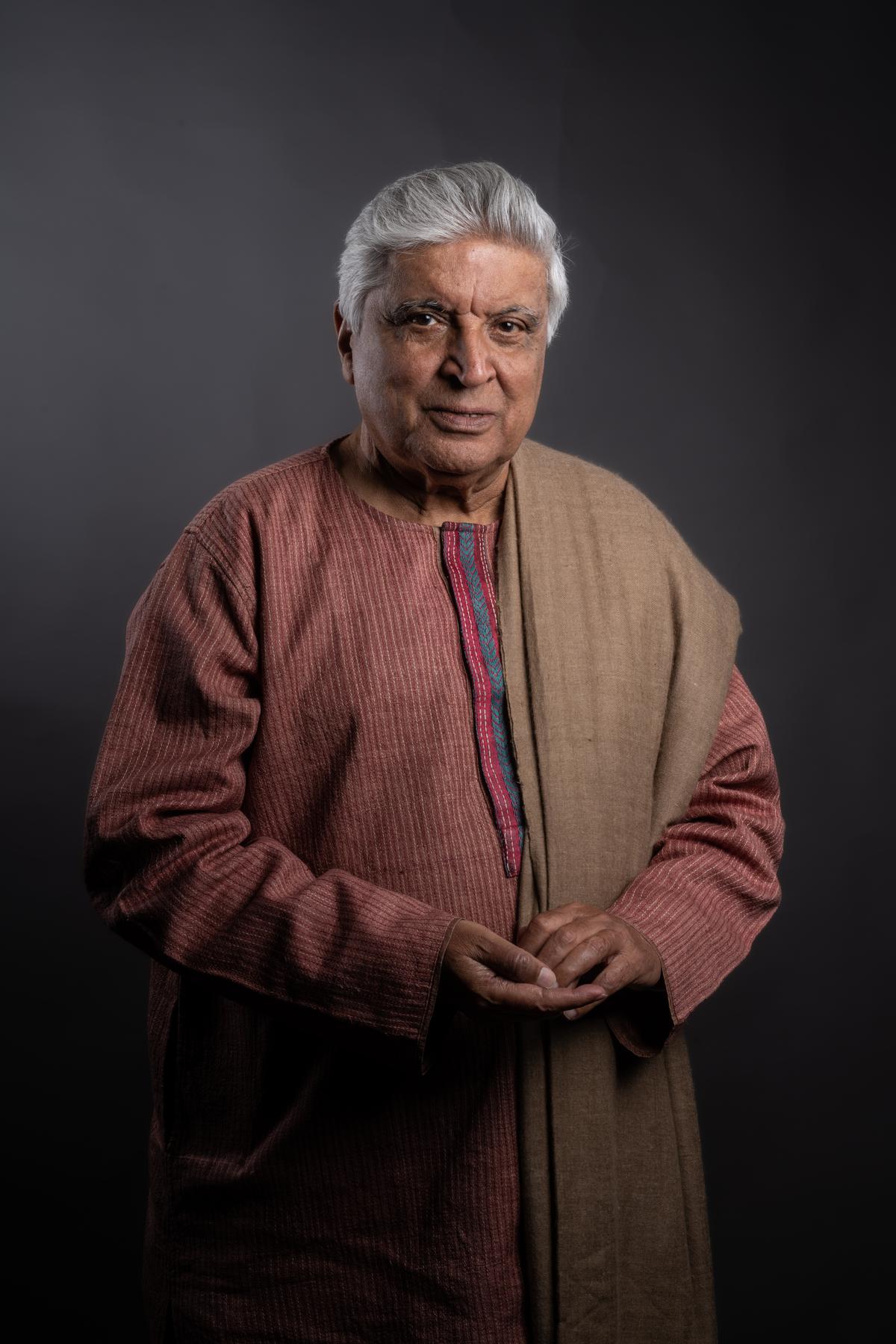

“This is long due especially since Indian music has reverberated across the world including ‘Naatu Naatu’ composed by M.M. Keeravaani and authored by Kanukuntla Subhash Chandrabose,” says Javed Akhtar, poet, lyricist, screenwriter and the chairman of IPRS, in a press release. “This forward-looking and exemplary judgement places the creator back at the heart of copyright creation which will serve as a great incentive for artistes, the music industry and for the creation of copyright in India.”

Javed Akhtar, poet, lyricist, screenwriter and the chairman of IPRS

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

The phrase of legislation

The Copyright Act of 1957 doesn’t account for artistes’ rights. In 1977, the Supreme Court in ‘IPRS v Eastern India Motion Pictures’ upheld the established order — that when an writer of any literary or artistic work indicators a contract, the copyright transfers to the producer and the writer loses any proper over their work, and by extension, royalties.

The 2012 modification sought to appropriate this imbalance by including two clauses and two subclauses. One of those acknowledged that the writer of a piece is the “first owner” of the copyright, and that the proper can’t be diluted even after a contract is signed. This intervention, nevertheless, didn’t carry a couple of decision. Producers used authorized ambiguity as an escape hatch. For occasion, the amendments got here into impact on June 1, 2012, leaving the destiny of contracts signed earlier than that date unclear. Ishaqzaade’s music, together with the evocative ‘Pareshaan’, is among the crowning jewels of Munir’s oeuvre, however she can not declare royalty for her songs as a result of the film was launched on May 11, 2012.

Efforts have been additionally made to low cost the legislation by misinterpreting a technicality. Two copyrights are generated for songs: one pertains to the sound recording, which belongs to the movie producer or music label, and the opposite to the creator for the musical and literary work. The argument went that radio stations have been utilizing already licensed sound recordings, which belonged to the producer or the label.

Give credit score the place it’s due

The April judgment is a battle received in a tough cultural and authorized struggle. “If you’re not giving credit to the creators, you can tell there is something really wrong with the industry,” says Gurbaxani.

There is benefit in introspecting the nuts and bolts of conventional hierarchies, a system constructed on limiting the diploma of management an artiste has over their work. Artistic work is seen as a commodity by producers and studios, which might be “transacted” by contracts or “bought out” by lump sum funds. Contracts are signed, then the songs are written, recorded and launched. “We start [our career] with giving away rights,” says lyricist and author Varun Grover, with movies resembling Udta Punjab and Badhaai Do to his identify. He isn’t certain at what level a music stops being his and belongs to a label as a substitute.

Lyricist and author Varun Grover

| Photo Credit:

Arunangsu Roy Chowdhury

“There was a time when Lata Mangeshkar put her foot down and demanded royalty for a song,” remembers movie critic Baradwaj Rangan. In the 1960s, when Mangeshkar was singing duets with the likes of Kishore Kumar and Mohammed Rafi, solely producers have been paid royalty. In an interview, she had recounted the interval as one which invisibilised singers and composers. In truth, the primary time she heard her identify hooked up to a music she’d sung was for the 1969 evergreen composition ‘Aayega aanewala’; the story goes that the radio station had obtained hundreds of letters asking concerning the singer and, finally, a line was inserted earlier than it performed: ‘This song is sung by Lata Mangeshkar.’

More lately, in 2019, Akhtar discovered his identify credited within the film PM Narendra Modi, when a remixed model of the music ‘Ishwar Allah’ that he wrote for 1947: Earth (directed by Deepa Mehta) was utilized in it. He argued that his “moral rights” as a creator have been breached (per the 2012 amendments, copyrights current a bouquet of rights: the ethical proper to 1’s work, the financial proper to profit from it, and the mental proper to be hooked up to it for posterity). It revived the talk across the diploma of management a creator has over their work.

Status at radio stations

“Out of more than 350 private radio stations in India, IPRS [so far] receives royalties only from two [Clear Media FM, Delhi, and Friends 91.9 FM, Kolkata],” says Rakesh Nigam, the CEO. In 2009, they filed a go well with in opposition to media homes Mathrubhumi and Malayala Manorama, which personal 94.3 Club FM and Radio Mango respectively in Kerala. A trial courtroom dominated in opposition to IPRS. In the same vein, musician and composer Ilaiyaraaja fought a case in opposition to Indian Record Manufacturing Co. Ltd. in 2020. The latter claimed possession of the breadth of music Ilaiyaraaja created for 30 function movies between 1978 and 1980. But the Madras High Court caught to the pre-2012 norm, sustaining that solely the producer of the movie held “first ownership”.

Passion doesn’t pay

There are manufactured information gaps throughout the industry about how copyrights and royalties function. “When contracts are drafted, there is no mention of royalties. And one is rather unaware if they are entitled to this compensation,” says Grover. “Lyrics writers are not really aware of royalties. We’ve been conditioned for years that only singers and composers are entitled to them.” It wasn’t till after his first album that he registered with IPRS.

“In the music food chain, writers are way down in terms of the importance given — even though a song begins with the writer. I hope we reach a stage where royalties are seen not as a burden or an infringement, but a simple right.”Kausar MunirLyricist

In the cultural creativeness, royalties are not often situated within the context of fair pay. There’s a fallacy that writing transcends capitalism and is about ardour, the next calling. Grover remembers when ‘Jiya Tu Bihar Ke Lala’ from Gangs of Wasseypur, his very first creation, performed on the radio. “I grew up listening to the radio. For me, it was a rite of passage that my song was played on it.” The query of royalties, he provides, was redundant at that second. “For a first-time lyrics writer, you’re counting your blessings and being happy about the exposure you’re getting via radio.”

But ardour and publicity can not maintain an individual. More so in an unorganised sector the place there are not any pensions or provident funds. The pandemic was a brutal reminder of this. When creators have been unable to work, IPRS distributed royalties (round ₹220 crore) from streaming and OTT platforms, as acknowledged of their Annual Transparency Report 2020-21.

In follow, royalties tether an writer’s id and craft with the work, transcending media and the occasions. “There will come a time when your relevance will be in question, when no one asks about you, but the royalties will continue because, once upon a time, you produced work that was relevant, which is still being heard by someone, somewhere,” says lyricist Kausar Munir, of Mrs Chatterjee vs Norway, Gehraiyaan, and Rashmi Rocket fame.

Lyricist Kausar Munir

Focus on mental property

Unlike a patent in science, artwork — particularly music, which flows by totally different media areas — is one thing that can’t belong to 1 particular person. “These laws were created at a time when the channels of distribution were limited to the radio or TV. Now, different platforms criss-cross through digital alleys,” says Rangan. The Bombay High Court’s verdict is an occasion of the legislation enjoying catch-up with the occasions. “This is a good judgment not because of what it does, but because of what it brings to light in terms of the complications of intellectual property in art. At least, people will start talking about [copyright and royalty] and taking it more seriously,” he provides. “It’s only right that it starts from the music industry because music is one of the immediate takeaways from a movie.”

Observers say the industry will profit from streamlining the method. According to Rakesh Nigam, CEO of IPRS, as an impartial musician who writes and composes their very own songs, and who isn’t registered with IPRS, there’s at the moment no possible option to gather royalties for the underlying works.

Rakesh Nigam, CEO of IPRS

| Photo Credit:

Akhil Raut

A way of group is important as a result of it fosters communication, consciousness and motion. In 2020, lyricists participated in a marketing campaign known as ‘Credit de do yaar’, urging streaming providers to say their names subsequent to a music. The marketing campaign obtained Spotify to start out displaying creators’ names. “Asking for and receiving credit can eventually result in getting royalties,” says Gurbaxani.

We might by no means resolve X; it’s an countless equation with countless variables. But, as Grover concludes, “It is a constant fight, it will evolve into varying beasts… and we are ready for it.”