Queer cinema continues to be ‘othered’ right into a sub-genre, with a sedate development in mainstream cinema. Funding continues to be the greatest impediment however not the just one. “Money is tied to things that are controlled by cis-hets who look at filmmaking from a certain perspective,” says filmmaker Onir, declaring that it’s a downside that arises from the notions amongst those that resolve what must be or shouldn’t be made.

Flumoxed over funding

Irrespective of being made by cis-gender heterosexual filmmakers (or if it has a cis-het gaze), what the current string of Hindi movies — like Shubh Mangal Zyada Saavdhan, Ek Ladki Ko Dekha…, Badhaai Do, Chandigarh Kare Aashiqui, Cobalt Blue, Maja Ma, and so on — proves is that if a producer and/or star again your movie, the theme being queer has fewer obstacles going ahead.

Are these releases a brief sample, or the begin of one thing larger? “A bit of both. Even if it is a trend, the more people venture into this, the more it will be seen as regular,” says Shubh Mangal Zyada… director Hitesh Kewalya, who provides that he acquired sufficient help from his producers to make the movie.

But one milestone isn’t sufficient in a multicultural nation like India, he says, and that any try, whether or not worthwhile or not, helps. “Earlier attempts like Aligarh, I Am, and Fire pushed the door for my film. So every step taken paves the way for the next.”

Hitesh Kewalya

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

What Hitesh says about the help of the producers can’t be undermined. When Prashanth Varma wanted to make Awe,not many have been snug with its queer theme, he says. “They thought that it was a joke because, in many Telugu films previously, queer ideas were used as jokes,” he says including that it issues having producers like actor Nani and Prashanti Tipirneni, who prioritise content material over earnings.

Unfortunately, there aren’t too many such backers. Some filmmakers, like Roopa Rao (of Gantumootefame), go for crowd-funding. Roopa made The Other Love Story in 2015 when the idea of an internet collection was nascent in India. Roopa needed to go on to the viewers; so she selected YouTube as a platform. “I started to gather funds from friends and family, and as word spread, strangers began pitching in, including a producer from the UK,” she says. There are additionally distinctive instances, like Shruthi Sharanyam’s B 32 Muthal 44 Vare, which had a trans-man as one among the leads, the place the Government helps with funds, one thing Roopa needs occurs extra.

Stills from ‘The Other Love Story’ and ‘B 32 Muthal 44 Vare’

| Photo Credit:

IMDb & Muzik247

Many queer filmmakers proceed to depend on unbiased sources. Filmmaker Sridhar Rangayan, who has been making movies for over 20 years, continues to supply his cash — he made his first movie, Gulabi Aaina, with a funds of two-and-half lakhs and his movies now value over a crore — from unbiased sources; even his subsequent movie Kuch Sapney Apne (a sequel to Evening Shadows) is funded by pals, household, and personal buyers.

What’s unlucky is that even should you lastly make an indie queer movie, Sridhar says, reaching the theatres is troublesome. “It’s not easy to recover the amount you invest in marketing. Moreover, multiplexes are dominated by bigger distributors who cater only to star-driven films. Theatres are now trying just to break even, they are not in the mood to support indie films.” Sridhar hopes to see devoted screens for indie movies like in the US.

Sridhar Rangayan

| Photo Credit:

Punit Reddy/Special Arrangement

Even Tamil filmmaker Sudha Kongara, who has made blockbusters with stars, says she doesn’t know what number of extra mainstream industrial movies she has to make, in order to facilitate a venture on the traces of her personal Thangam (the story of a trans-person from Netflix’sPaava Kadhaigalanthology) to hit theatres. “It’s still a chip on my shoulder that you have to be commercially viable, to do something you actually want later,” she says. “Even the OTT players ask me for commercially-viable content like what I put out in theatres.” She provides that the streamers are additionally star-driven now.

Nevertheless, Sridhar rests his hope on streaming platforms. “My first queer film, 2003’s Gulabi Aaina, was refused a censor certificate. We had to go through community-based organisations to screen it at film festivals. Only in 2015, when Netflix entered India, did the film get a release on OTT,” he informs.

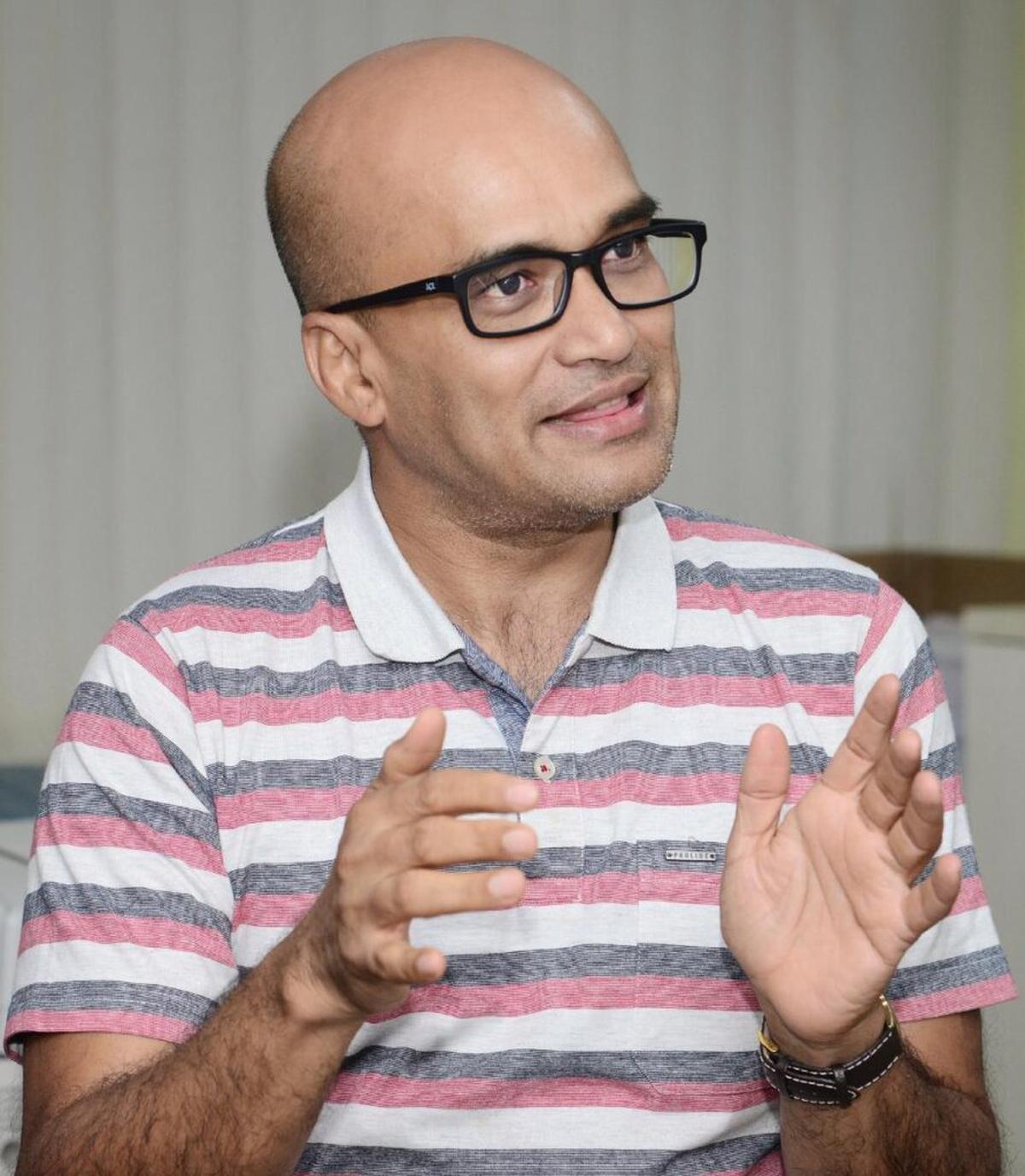

However, Sridhar and plenty of others say that the area on OTTs is shrinking as properly. “Whenever I pitch something, they say, ‘We’re only taking baby steps,’ but their platform already has content that is far more provocative, which people are watching,” says Onir.

Onir

Time for extra stars to shine?

So, whereas it tries to bypass the star-driven system, ought to queer cinema additionally create its personal stars? Onir says that it will depend on society’s acceptance. “We are living in a country where actors don’t want to come out because of the state of acceptance.”

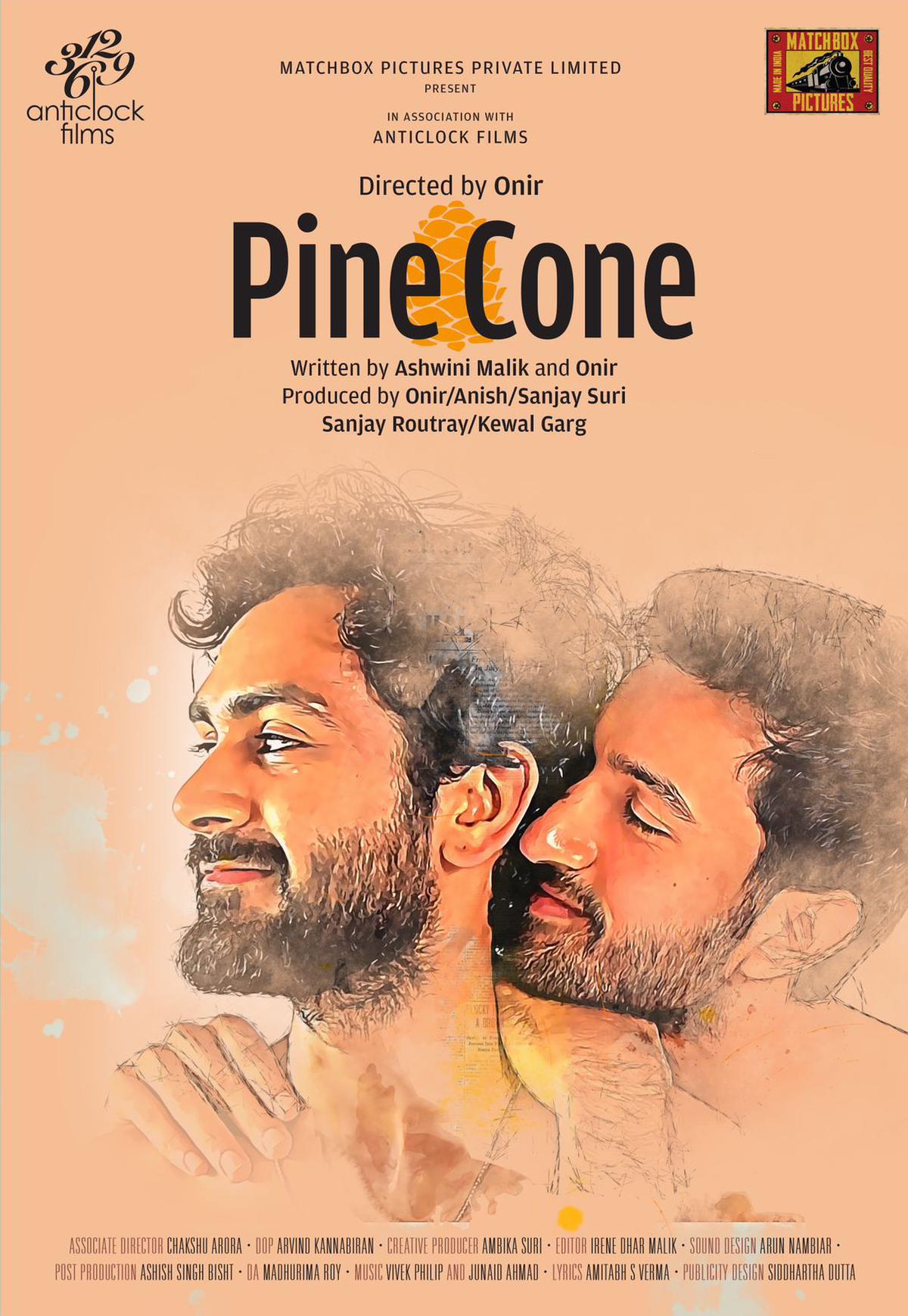

Open-and-out queer actors, filmmakers, and producers are the want for the hour. Adds Onir, “We need more people from the community to talk about their lived-in experiences. That’s why it was important for me to cast a queer actor in Pine Cone.” Onir’s newest is headlined by Vidur Sethi, the first overtly homosexual Bollywood actor.

What does that must do with queer cinema discovering success in the mainstream? Rather a lot.

Queer filmmakers in the mainstream

Poster of ‘Pine Cone’

| Photo Credit:

@IamOnir/Twitter

Firstly, a lift in the mainstream could be counterproductive if most queer content material is from cis-het filmmakers who inform queer tales from their perspective. For occasion, Sridhar factors out how most ‘Bollywood queer films’ are household dramas with just some queer components thrown in. “Other elements are narratives structured around these themes, not vice-versa.” Or as queer Kannada author Vasudhendra says, it appears as if most cis-het filmmakers “imagine a cis-man-cis-woman relationship and just swap the gender of one of them,” which fences the actual experiences of queer.

It’s akin to cis-men trying to make the new-age feminine motion star come throughout as a gender swap with the hyper-masculine male hero, or as Sudha places it, “semi-pseudo male characters,” and declare that to be progressive characterisation. The presence of queers will guarantee the mainstream area is devoid of queerphobic concepts, that are nonetheless prevalent in cinema (as current as this yr’s Telugu launch Ramabanam)

Vasudhendra

| Photo Credit:

Ramakrishna Sidrapal/Special Arrangement

But Vasudhendra doesn’t consider that queers ought to solely make queer movies. “If a story is about a cis-woman who has married a gay man, it’d be better if she tells the story from her point of view.” But solely when queers begin telling their tales will others study their perspective and attempt to do higher, he provides. “It’s like how the earlier Dalit stories, that were written by non-Dalits, were mostly sympathy showers with no nuances of the life of Dalits. That changed. So did stories of women. So should be the case with queer stories.”

Sudha understands this. The filmmaker met trans individuals and took six months to arrange for her quick in Paava Kadhaigal. “But I will never know if I am doing justice to it. I am someone who will have qualms with that.”

Some producers see queer cinema as mere tokenism. “Many a time, they are like, ‘Hey, we have done one queer film, and we’re done.’ Are our lives so plain and homogeneous that you make one story and it’s done? They don’t tell a straight director, ‘We’ve already done 10 straight stories,’ right?” questions Onir.

Sudha Kongara

| Photo Credit:

Pichumani Ok/The Hindu

Tokenism in queer cinema

There is an concept that’s floating round on how queerness can attain the mainstream; just like having cis-gender women and men play supporting characters, can’t we’ve queer characters as properly in motion pictures led by cis-genders? Would that not assist in normalising queerness in a cis-heteronormative area?

Filmmakers warning that such writing may quantity to tokenism if not given its due respect and dignity. Onir wonders if because of this the queer character’s queerness is to be watered down. “Have you ever heard someone say that this person is not wearing his straightness on his sleeve? Why does my life have to be subtle? So, a queer character should be treated with as much dignity as you treat other characters,” he says.

It can be necessary that queer characters don’t search validation from cis-het society. “Everything about us is not about them; we are leading our lives as well.” And he additionally factors out that such makes an attempt be not put as ‘having queers in films that do not speak about queer issues’. “I hate the word ‘issue’. What ‘queer issue’ do films like Call Me By Your Name or the French film Close talk about? Not all heterosexual stories are about ‘issues’. Why is my life an ‘issue’?”

A nonetheless from ‘Close’

| Photo Credit:

Prime Video

Acceptance in society

All this discuss finally rests on the viewers of a movie and the way society accepts queers. On that entrance, many appear pragmatically optimistic. “Ten years ago, if I went to a public institution and asked them if I can speak about queerness, they’d reject the idea without a second thought. But now, many colleges are requesting me to come and speak about it. Society is gradually opening up,” says Vasudhendra.

Cinema and popular culture play a significant position in this, and it’s as much as the collective society to make sure that there are extra avenues for queer tales, extra space for queer discourse and extra queers telling their tales.