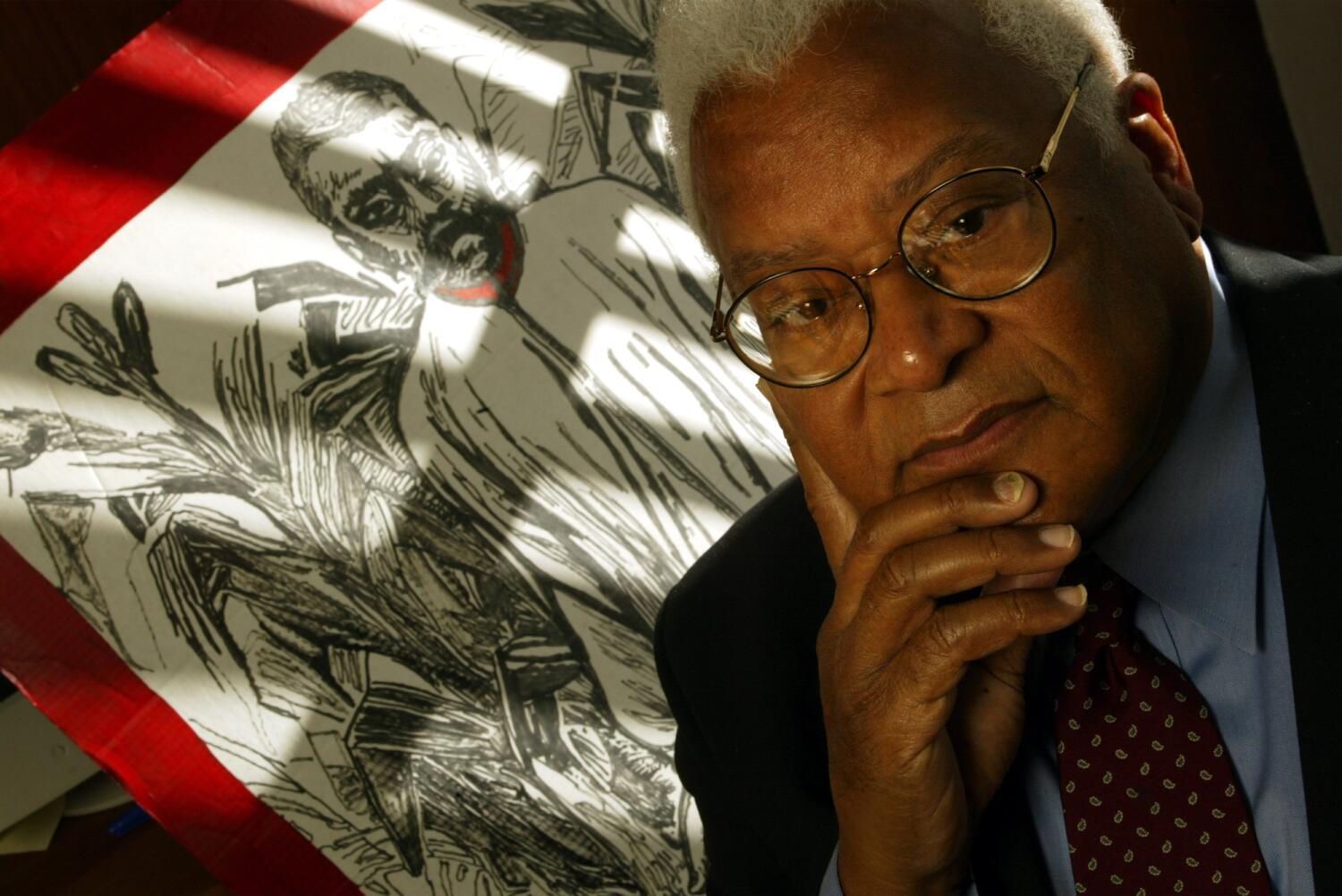

James M. Lawson Jr., a Methodist minister who turned the trainer of the civil rights motion, coaching tons of of youthful protesters in nonviolent techniques that made the Nashville lunch counter sit-ins a model for fighting racial inequality within the Sixties, has died. He was 95.

Lawson, who for a long time labored as a pastor, labor motion organizer and college professor, died Sunday of cardiac arrest en path to a Los Angeles hospital, his son J. Morris Lawson III instructed the Washington Post.

Recruited by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Lawson organized and led weekly workshops on nonviolent motion in Nashville and different sizzling spots of the motion. The workshops educated many future leaders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, together with Rep. John Lewis.

“I truly felt … that he was God-sent,” Lewis as soon as wrote of Lawson. “There was something of a mystic about him, something holy, so gathered, about his manner…. The man was a born teacher, in the truest sense of the word.”

Called “the leading nonviolence theorist” by King, Lawson had studied Gandhi’s philosophy in India earlier than becoming a member of the battle within the South. He led seminars all through the area and have become a roving troubleshooter for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

In 1968, he invited King to talk to hanging sanitation staff in Memphis, the place the charismatic preacher, who had anticipated his personal demise, was assassinated.

Lawson labored with numerous civil rights teams within the South till 1974, when he moved to L.A. to turn out to be pastor of Holman United Methodist Church. He led the church for 25 years. He retired in 1999 however remained an activist for peace and social justice.

Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass, in a assertion Monday, stated, “Reverend James Lawson Jr.’s life and legacy reverberates in the continuing movement to advance social and economic justice in Los Angeles and beyond. He dedicated his life to equality and justice and helped train a generation of national leaders. … These teachings changed the course of history.

“Here in Los Angeles, Reverend Lawson taught many activists and organizers and helped shape the civil rights and labor movement locally just as he did nationally. … Reverend Lawson was also an invaluable mentor to me — I continued seeking his counsel throughout my time as an organizer, an activist and as an elected official. He was there for me as I know he was there for countless civic and faith leaders here in Los Angeles who were guided and influenced by his teachings.”

James M. Lawson Jr., the son of a proud Black preacher, didn’t at all times follow nonviolence. As a younger boy in Ohio within the Thirties, he smacked a white little one for shouting a racial slur at him.

Luckily for Lawson, there have been no repercussions — till he obtained residence.

“Jimmy,” his mom stated when he instructed her what he had executed, “what good did that do? There must be a better way.”

Busy within the kitchen, she didn’t have a look at him when she delivered her reprimand, however her phrases resonated. Lawson felt his world “just sort of stopped,” he later recalled. “And somewhere way in the deep of me I heard myself saying, ‘I will find that better way.’”

His search led him to India, the place he studied Mohandas Ok. Gandhi’s concepts about nonviolent resistance. After returning to the United States, he utilized what he had discovered to the civil rights motion, mixing Gandhi’s rules with biblical insights to turn out to be what the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. would name “the leading nonviolence theorist” of the period.

Lawson was a pivotal determine in among the most vital campaigns of the motion, together with the Nashville lunch counter sit-ins, the primary Freedom Ride and the social justice battles he led as pastor of Holman United Methodist Church in L.A.

The Montgomery bus boycott King launched in 1955 had proved the efficiency of nonviolent protest. But it was Lawson who introduced disciplined instruction to the youthful protesters who would take the civil rights motion to the following stage. He taught them not solely the lofty rules of passive resistance but in addition basic techniques, together with face up to taunts and bodily assaults, keep away from breaking loitering legal guidelines, “even how to dress” for a sit-in, historian Taylor Branch wrote, which meant “stockings and heels for the women, coats and ties for the fellows.”

His nonviolence workshops nurtured most of the leaders who would propel the motion within the Sixties, together with Lewis, who was one of many organizers of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

“I couldn’t have found a better teacher than Jim Lawson,” Lewis wrote in his 1999 memoir. “It is not hard to find forgiveness. And this, Jim Lawson taught us, is at the essence of the nonviolent way of life.”

Born Sept. 22, 1928, in Uniontown, Pa., Lawson grew up in Massillon, Ohio, the son of a Jamaican-born seamstress and an itinerant Methodist minister who packed a gun when he traveled within the South. His father “believed that I should fight to defend myself,” Lawson, the sixth of 9 youngsters, recalled in a 2000 interview with National Public Radio.

He was in highschool within the Nineteen Forties when he staged his first sit-in, focusing on a Massillon restaurant that refused to serve Blacks. The proprietor served him however instructed him by no means to return again.

After highschool, he attended Baldwin-Wallace College, a Methodist school in Berea, Ohio, and joined the pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation. When he was referred to as to army obligation throughout the Korean War, he refused the draft and was despatched to jail for 14 months.

In 1953, Lawson joined a Methodist mission to India and devoted himself to finding out Gandhian nonviolence. He was nonetheless in India in late 1955 when he learn a newspaper story concerning the Montgomery bus boycott. “I saw that as an answer to a prayer,” Lawson, in a 1984 Times interview, stated of the protest that was led by King. “My reaction was to start shouting for joy.”

He returned to the U.S. in 1956 and enrolled within the Graduate School of Theology at Oberlin College, the place he met King in 1957. King, who had come to Oberlin to talk, urged Lawson to hitch the motion.

In 1958, Lawson moved to Nashville and enrolled in Vanderbilt University’s divinity program. He additionally joined the Nashville Christian Leadership Council and commenced holding workshops on nonviolence.

Lawson relied closely on role-playing, and infrequently requested college students to taunt others with racial insults to assist them be taught self-restraint. He confirmed the scholars run an orderly sit-in by filling lunch counter seats in shifts. He additionally confirmed them methods to reduce accidents by sustaining eye contact with their assailants and utilizing their our bodies to assist distribute the blows that have been certain to return.

In November 1959, Lawson’s college students staged three follow sit-ins. “We just did it quietly,” with out press protection, he instructed The Times in 2014. “We called them part of our discovery process.”

He minimize brief the coaching interval after college students in Greensboro, N.C., obtained nationwide media consideration with a sequence of impromptu sit-ins that started on Feb. 1, 1960. A couple of weeks later, the Nashville college students — a “nonviolent army” about 500 robust, drawn from Fisk University and different native faculties — leaped into motion, occupying three downtown Nashville lunch counters. Over the following three months, extra institutions have been focused, together with bus terminals and main shops.

“It was clear we had a very disciplined movement … with students as our primary energy,” Lawson stated.

When 81 college students have been attacked by a group of whites and subsequently arrested, Lawson was expelled from Vanderbilt. Faculty members resigned in protest, producing headlines throughout the nation.

The turning level got here when the house of an legal professional for the jailed protesters was bombed, triggering a mass march to Nashville City Hall and a boycott of white-owned companies. In May 1960, three weeks after the mayor appealed to white residents to finish discrimination, Nashville lunch counters started to serve Blacks and sit-in campaigns quickly unfold to dozens of different Southern cities.

Lawson believed that sit-ins have been more practical than lawsuits, which he criticized in a 1960 speech at Shaw University in North Carolina as “middle-class conventional, halfway efforts” to cope with grave social injustice.

Longtime activist Julian Bond recalled in “Voices of Freedom,” an oral historical past of the motion, that Lawson sounded “like the bad younger brother pushing King to do more, to be more militant” and had “a much more ambitious idea of what nonviolence could do.”

The day following Lawson’s speech, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was based with a assertion of goal drafted by Lawson. Initially led by Marion Barry, the long run mayor of Washington, SNCC helped drive main civil rights campaigns, together with voter registration initiatives and the 1961 Freedom Rides.

When the primary Freedom Ride was derailed by mob violence, a small group of Nashville college students educated by Lawson accomplished the damaging bus journey from Montgomery, Ala., to Jackson, Miss. Lawson accompanied them and was arrested together with different Freedom Riders in Mississippi after among the protesters entered the whites-only restrooms on the Jackson terminal. At Lawson’s urging, they refused bail, which impelled tons of of different college students to hitch the campaign in opposition to segregated interstate journey.

In 1962, Lawson turned pastor of Centenary United Methodist Church in Memphis. He left for L.A. in 1974 when he was employed to guide Holman United Methodist Church.

Over the following 25 years, till his retirement in 1999, he remained a outstanding activist. He was co-chair of the Gathering, a group of 200 South Los Angeles clergymen who protested the Los Angeles police capturing of Eula Love in 1979, and headed the Los Angeles chapter of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. He was arrested a number of occasions at protests, together with a rally in opposition to U.S. army support to El Salvador within the late Eighties. In 2000 he risked a church trial for blessing a lesbian wedding ceremony.

After Lewis died in 2020, Lawson, on the age of 91, paid tribute to the congressman alongside three former U.S. presidents at a memorial service at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta. In an eloquent eulogy bookended by the poetry of Czeslaw Milosz and Langston Hughes, he exhorted Americans to “practice the politics of the preamble to the Constitution” because the “only way” to honor Lewis’ life.

He stated he had no regrets concerning the fateful invitation he prolonged to King to deal with hanging sanitation staff in Memphis in 1968. King was assassinated there a day after giving his well-known “Mountaintop” speech, during which he spoke of his dream of equality and added, “I may not get there with you.”

“Martin expected his death,” Lawson instructed The Times in 2004. “I don’t know if he specifically expected it on that day, but he had known since Montgomery that he could be shot down … any time.”

Wondering what sort of particular person would commit such a crime, Lawson started visiting the convicted killer, James Earl Ray, in jail. He got here to imagine, as did members of the King household, that Ray was harmless and pushed unsuccessfully for a new trial. When Ray determined to marry a sketch artist who had lined his arraignment, he requested Lawson to conduct the jail ceremony.

“It was not just that I doubted his guilt; it went far beyond that,” Lawson instructed historian John Egerton years later. “I knew that if Martin were alive and in my position, he would have married them even if he knew Ray was guilty. As one of my sons said to me, ‘If you believe all that stuff you’ve been preaching, you’ll do it.’

“He was right, of course.”

Lawson is survived by his spouse, Dorothy Wood, and two sons, J. Morris Lawson III and John Lawson; a brother, Phillip; and three grandchildren. His son C. Seth Lawson died in 2019.

Woo is a former Times employees author.