In a snowy clearing near Ely, Minnesota, two scientists examine a moose calf, which is now almost 500 pounds at just nine months old. The female calf has been temporarily sedated to allow biologist Morgan Swingen and veterinarian Mary Wood to fit her with a tracking collar. Soon, she’ll wake up and dash back to her mother.

“The collar helps us track her location and gather data on her habitat use,” says Swingen, a member of the 1854 Treaty Authority. “If the collar stops moving, it usually means the moose has died.”

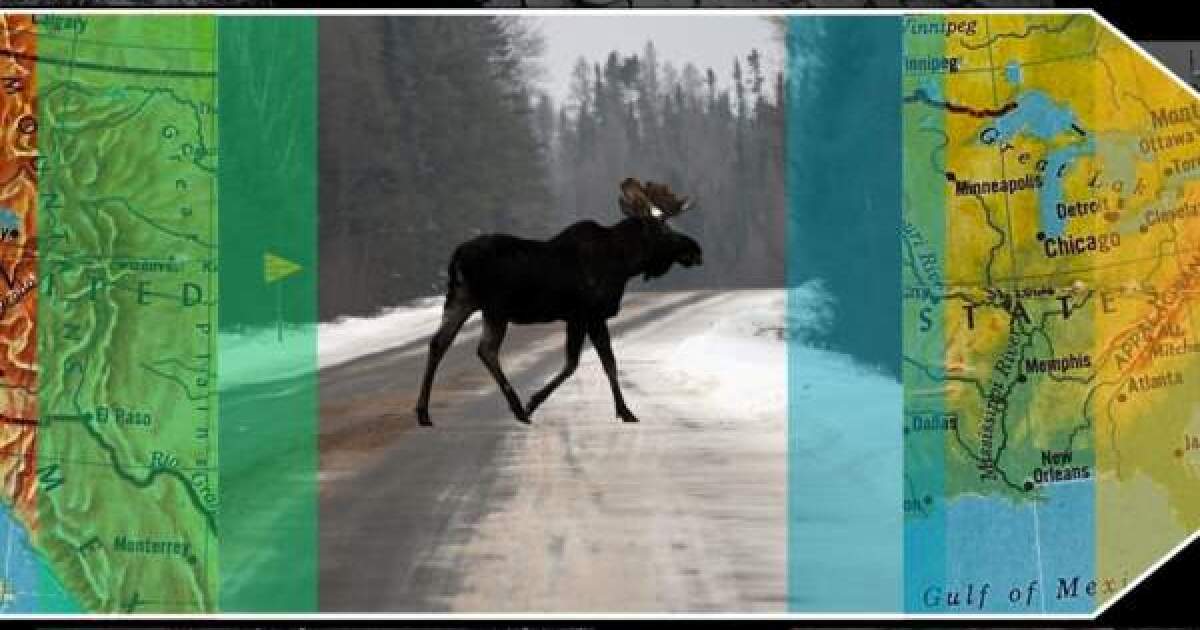

Moose numbers in Minnesota have drastically decreased, now about half of what they were two decades ago. While conservationists are having some success stabilizing the population, moose face threats from parasites, predators, and climate change.

After collaring the calf, Swingen and Wood regroup in an ice fishing trailer adapted as a mobile lab—essential for scientists studying and tracking Minnesota’s moose. They use a spotter plane equipped with an infrared camera to locate animals in the wild.

Helicopter pilot Seth Moore notes, “Flying in these conditions can be brutal. The temperature today is about five degrees Fahrenheit, and we have no doors.”

This harsh environment complicates their study, which aims to understand what limits moose populations, particularly juvenile moose. Michelle Carstensen, from the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, describes juvenile moose as the population’s future. “We need to ensure they survive the winter to contribute to the population growth.”

The team has already collared 54 moose, continuing their research as climate change makes the situation more urgent. Bitter winters and tick infestations are increasingly common, endangering these majestic creatures. Studies indicate warmer temperatures lead to more winter ticks feeding on moose, affecting their health and survival.

“We’re at the edge of the moose’s range in North America. Even slight environmental changes can significantly impact their survival,” Carstensen explains.

The situation is not all bleak. Conservationists are changing how they manage habitats. By preserving areas like the 18,000-acre Sand Lake/Seven Beavers preserve, they’re attempting to restore ecosystems that benefit moose. Chris Dunham from The Nature Conservancy finds promising signs. Areas affected by a 2021 wildfire are regenerating, creating new food sources for moose.

“You can see young, vigorous aspen sprouts up,” Dunham says. “This habitat is ideal for moose.”

Moose primarily eat woody plants; an adult can consume over 70 pounds a day. However, they also require shade in summer and wetlands, making habitat management essential for maintaining biodiversity.

Despite their efforts, the increasing deer population poses additional challenges. Deer carry parasites that are deadly to moose, and a greater deer presence can also attract more wolves, which prey on calves. But Dunham has noticed that hard winters have reduced deer numbers, providing temporary relief.

The multi-year study focuses on juvenile moose, whose survival can determine the population’s future. “It’s like a wildlife CSI,” Carstensen adds. “We aim to identify factors affecting their survival.”

In the ice fishing trailer turned field lab, the team is determined. They are documenting everything meticulously, gathering data that could provide insights into the moose’s health and survival.

As climate change continues to affect the ecosystem, their studies grow more urgent. “We’re learning how to manage the forest to aid moose, especially in the face of climate change,” Dunham says optimistically.

Moore emphasizes the importance of preserving moose populations for future generations. “One principle in Ojibwe philosophy is planning for the Seventh Generation. We owe it to our future to care for this land and its creatures.”

Conservation work continues as experts strive to protect the moose habitat while we still can. For more information about supporting wildlife conservation efforts, visit The Nature Conservancy.